Honolulu, Hawaii

The Honolulu metro area, which comprises the entire island of Oahu and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, has long stood out as home to one of the largest Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) populations in the United States. As of 2019, Metro Honolulu was the only region where AAPIs comprised a majority (52 percent) of the entire population. At the same time, Hawaii has been home to a housing crisis for the last half century, fueled in no small part by a tourist economy that leaves many local workers struggling to afford local housing costs. Moreover, these deep-seated structural inequalities in housing and employment are the latest iteration of a centuries-long colonial project that has continually disenfranchised and dispossessed the islands’ indigenous inhabitants.

The islands’ large, diverse, and longstanding AAPI communities are the direct result of Western settler colonialism in Hawaii, starting with the “discovery” of the archipelago by James Cook in the late 1700s. Alongside Christian missionaries, white Americans and European plantation owners came to claim large swaths of territory across the islands, which in turn led to the migration of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino workers to serve as low-wage agricultural laborers. In 1893, a cabal of American and European settlers illegally overthrew Hawaii’s constitutional monarchy, deposing Queen Liliuokalani and leading to the US territorialization of the islands five years later. US imperialism in Hawaii has taken many forms, including the establishment of military bases, the mass depletion of the native Hawaiian population, and the ongoing dispossession of indigenous lands and devastation of ecological spaces.

Over the long arc of Hawaiian history, these colonial projects and migratory patterns have led to demographic and socioeconomic trends that are somewhat at odds with one another. The longstanding presence of many different Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiian communities means that many AAPIs have become prominent members of Hawaii’s political and business worlds. Many Asian American and non-native Pacific Islanders in Hawaii have become part of the multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual polity that makes up the islands’ “locals.”

At the same time, however, local advocates note that an umbrella term like “AAPI” has no real meaning in Hawaii, as the term obscures the class hierarchies and cultural distinctions between the many Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Native Hawaiians who live on the islands. Many Asian American residents, including those with deep roots in Hawaii, have become part of the ownership and landlord class that contributes to the ongoing economic exploitation and territorial dispossession of native Hawaiians. While socioeconomic disparities exist between indigenous Hawaiians and other Pacific Islander communities, local advocates note the comparatively vast class divide between Pacific Islanders and East Asian Americans. In this light, Asian Americans may be complicit in the colonial project that native Hawaiian sovereignty movements have long sought to end.

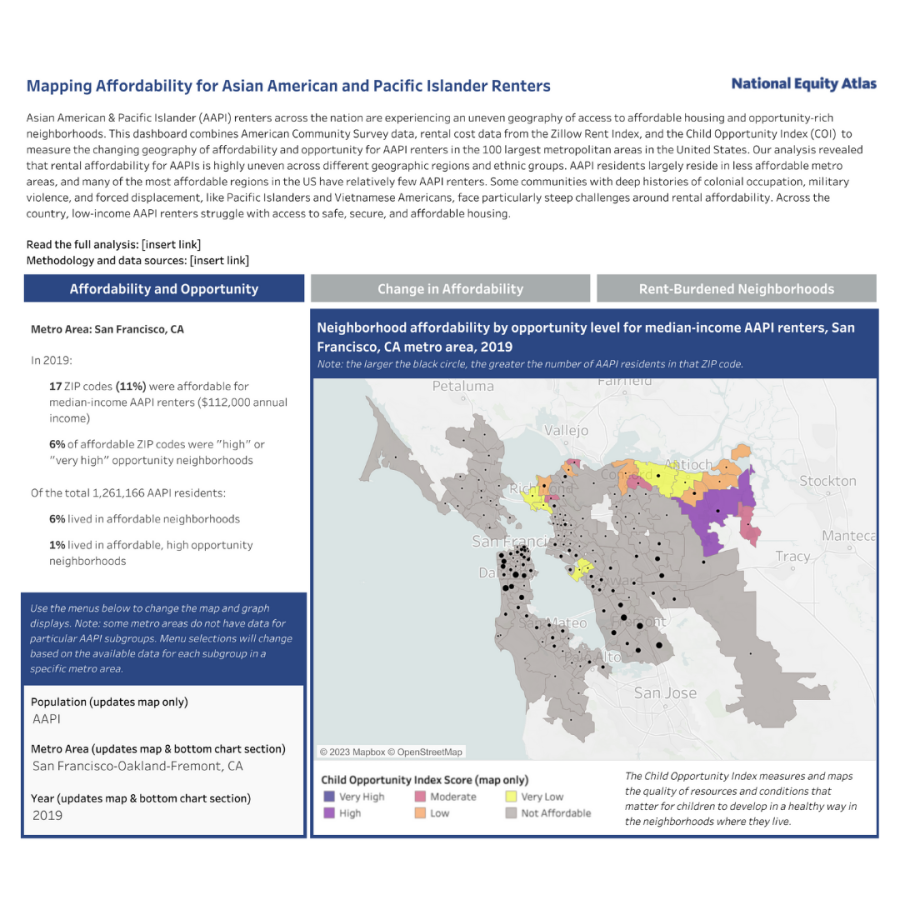

A confluence of factors — the primacy of the local tourist economy (e.g., hotels and short-term rentals), the in-migration of well-off newcomers, and the too-slow pace of new housing construction to meet demand — has led to a situation where nearly the entirety of Oahu is unaffordable. In 2019, only 4 percent of AAPI residents in Metro Honolulu lived in zip codes that were affordable for median-income AAPI households, and there was not a single neighborhood on the island affordable for median-income Pacific Islander, Vietnamese, or Korean households. While three-quarters of AAPIs on Oahu live in zip codes that are high opportunity (based on the Child Opportunity Index), high housing costs are an inescapable feature for people living in the Honolulu metro area.

One consequence of the long-term housing crisis is the severe overrepresentation of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPIs) among the island’s unhoused population. NHPI residents make up 10 percent of Oahu’s overall population but 35 percent of the island’s unhoused people, according to the 2022 point-in-time homelessness count for Oahu. A broader repercussion, for native and non-native Hawaiians alike, has been a net loss of residents due to out-migration in recent years. This exodus of residents, including many young people, has threatened the local workforce and has contributed to the ongoing diaspora of native Hawaiians, such that half of all native Hawaiians now live away from the islands.

The particular colonial and labor histories of the Hawaiian islands make AAPI housing equity a unique conundrum in Hawaii, as it invokes the question: Equity for whom? If housing was more affordable, would that spark even more non-locals with purchasing power to move to the islands, thereby reinforcing the issue of housing scarcity? Do affordable housing development and tenant protections that aid locals regardless of race complicate indigenous land sovereignty movements? What does indigenous sovereignty look like, given the deep-rooted nature of a multiethnic polity whose ancestors arrived in Hawaii as a consequence of Western colonialism? Approaches to housing justice in Hawaii must take stock of these particular challenges.

Gavin Thornton, the executive director of the Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice, contributed observations and insights to this profile.